The predawn rumble of pesticide-spraying trucks is a rite of spring in almost 200 Massachusetts communities. Some $11 million is spent in the state each year controlling and counting the pests and educating residents about how to avoid contracting mosquito-borne diseases such as West Nile virus.

Yet no state funds are dedicated to tick-borne diseases, one of which, Lyme, infects at least 5,500 residents a year in Massachusetts and likely many more. Residents may notice that gap even more this spring: The winter’s deep snow probably insulated ticks from low temperatures and heavy winter mortality, say some entomologists.

Ticks and Lyme have spread across Massachusetts in the past 40 years to become one of the region’s most commonly reported infectious diseases, yet the state’s public health priorities have not kept pace. Two years ago, a special state Lyme commission suggested a modest investment of less than $300,000 for a public education program, yet no money has been set aside, and the commission’s other specific recommendations – from promoting more awareness in the medical community to better disease surveillance – have not been adopted.

READ MORE FROM NECIR: Can you trust Lyme disease tests?

“The state needs to step up to the plate,’’ said Larry Dapsis, deer-tick project coordinator and entomologist for Barnstable County, which funds the state’s only county tick-education program. Tracking the West Nile virus in mosquitoes that can make humans sick can be like “looking for a needle in a haystack,’’ Dapsis said. “For ticks we look at the landscape and, well, it’s scary.”

There are at least six tick-borne diseases in Massachusetts, and experts expect more soon: The Lone Star tick, which can transmit several pathogens and spark a bizarre allergy to red meat, took up residence on the Massachusetts mainland last year in Sandy Neck Beach Park in West Barnstable. A new human tick-borne disease – borrelia miyamotoi – was reported in the Northeast in 2013 and is being found in people in Massachusetts: In 2014, Cape Cod Hospital had 26 cases.

“When we do surveillance on mosquitoes, we are also trying to communicate risk to people and tell them how to avoid contracting the disease; that is missing with ticks,’’ said Chris Horton, superintendent of the Berkshire County Mosquito Control Project in Pittsfield, one of the state’s 11 regional mosquito control districts. Berkshire County has the highest incidence of anaplasmosis, a tick-borne illness that can cause fever, chills and confusion, with 41 cases per 100,000 residents in 2013. In Hampshire and Worcester counties, it is less than 2 cases per 100,000 residents, some of the lowest in the state.

U.S. & World

Few argue against mosquito control in Massachusetts. Started out in part because of the nuisance factor, it has evolved to try to limit disease threats to the public. And, many argue, it works: Usually less than 30 people a year are reported to contract West Nile and even fewer get Eastern Equine Encephalitis.

State Representative Carolyn Dykema, a Holliston Democrat, filed a bill this year for the third time to expand the authority of the mosquito districts to include ticks, but few tick experts expect it to gain traction.

“(Ticks) are very different to control,’’ compared with mosquitoes, Horton said. For example, mosquitoes are airborne at specific times of day at which they can be targeted with pesticides, he said, and larvaeside can be sprayed in standing water where they breed. Ticks are not very mobile, can be found throughout landscapes, and populations can dramatically vary even within short distances.

State officials receive about $40,000 in federal dollars a year to help support Lyme disease surveillance and education, and officials say other duties around Lyme are not covered by any specific state line item but is part of the department’s general funding.

Largely, state officials say they are focusing on educating residents to protect themselves with tick checks, covering up when outside, and using tick-killing sprays on footwear and outerwear.

“We consider the outreach we do critically important – and that has not stopped,’’ said Katie Brown, the state’s public health veterinarian. A state epidemiologist, she said, is now developing multimedia tick education presentations that schools can borrow, and officials created public service videos last year that are available for local boards of health and to the public.

Northeast states, in general, don’t spend much to prevent tick-borne diseases, although Maine voters in November approved $8 million for a lab that will test ticks and conduct other research at the University of Maine in Orono by 2017.

In Massachusetts, an $111,000 Community Innovation Challenge grant last year subsidized testing costs of ticks to track what pathogens and parasites were being found in 32 communities. Findings of the testing at the Laboratory of Medical Zoology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst included: the discovery of Lone Star ticks in counties in which they had previously not been recorded (they are considered resident in only Barnstable County); that ticks harboring more than one pathogen that can cause illness in humans are present throughout the state; and that those most frequently bit by ticks appear to be children and older people.

While Stephen M. Rich, the laboratory director and other tick experts were hoping the testing would continue to be funded, the state canceled the entire grant program this year. The lab still tests ticks for a $50 fee for residents who mail them in, and Rich is still working to grow the program. He said that to have a robust tick surveillance and prevention program, all a town would need to do is devote $1,000 to $3,000 of their state funding.

“To establish a disease surveillance and prevention system, like the one we have for mosquitoes, will require enabling legislation that allows towns to subsidize this service that Massachusetts residents want," Rich said in an email.

A controversial illness

Lyme Disease is one of the most vexing public health issues in Massachusetts. First discovered in a group of children in Lyme, Conn. in the mid-1970s, it has spread throughout every community in Massachusetts and much of the Northeast.

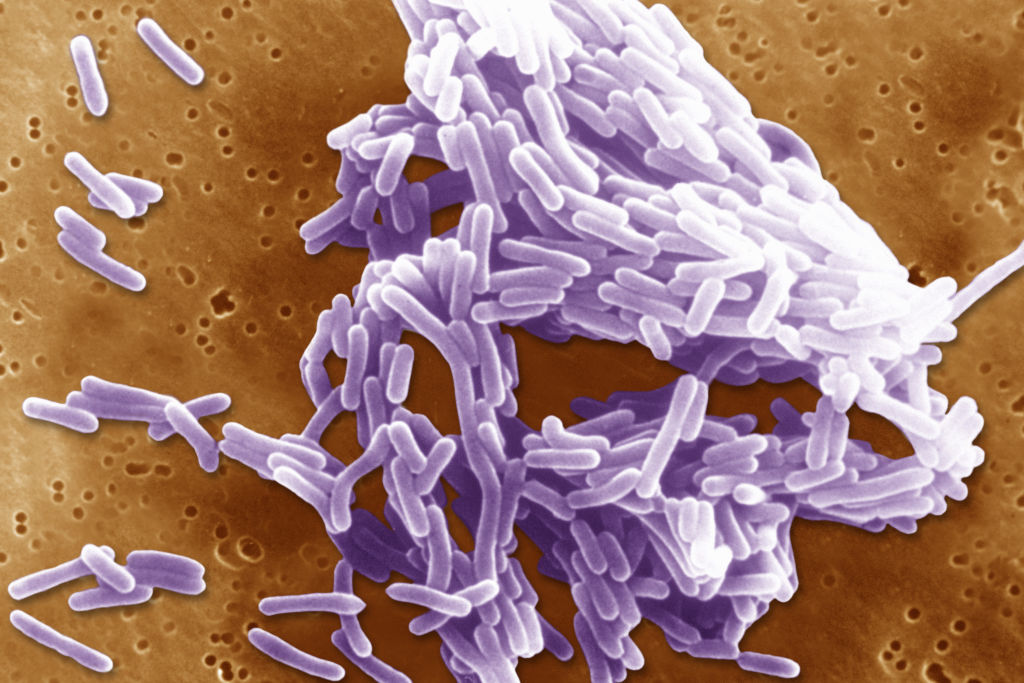

Deer ticks – often no bigger than the size of a poppy seed – become more active as the weather heats up, latching onto pets and people as they pass through forested areas and tall grasses. As the parasites feed on blood, they can pass pathogens to people that sicken them, the most common of which is Lyme.

Early symptoms of Lyme can include a skin rash that looks like a bullseye, headache, fatigue, and fever. If caught early, a month or less of antibiotics cures most cases, but if the infection is left untreated, it can spread to the joints, heart and nervous system, causing such symptoms as facial paralysis, arthritis and tingling sensations, and in very rare cases, death.

READ MORE FROM NECIR: Study finds cancer diagnoses delayed because of chronic Lyme misdiagnosis

There were 5,665 confirmed and probable cases of Lyme in 2013, the last year of available data, but federal officials say the number of cases is underreported. Two years ago, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, using a new way of measuring Lyme disease diagnoses, said cases of Lyme were likely 10 times more common than previous national counts, affecting possibly 300,000 people a year in the U.S., the bulk in the Northeast. By that measure, the number of Lyme cases in Massachusetts would be about 50,000.

Communities trying to fill the gap

In the absence of any dedicated state program or funding, communities, individuals, Lyme patients and health associations are, themselves, attempting to educate residents.

The first Central Massachusetts Lyme Conference was held in Worcester in March. The Massachusetts Association of Public Health Nurses is holding a daylong Brewster seminar on Lyme and other tick-borne disease on April 16. In North Andover, the public health nurse is developing prevention materials to be placed in the library and other public places. In Medfield, residents are discussing whether to spray for ticks on the perimeter of two playing fields.

Such patchwork attempts, however, have not yet appeared to result in any reduction of tick-borne disease statewide, according to statistics.

“It really comes down to a budget item,’’ said Chris Kaldy, chair of the Medfield Lyme Disease Study Committee. The community works hard at tick education, that includes providing tick check cards for first- and third-graders to bring home. Kaldy would like to do more, but, she said, “We don’t have the money to do mailings (and) other ways to get the word out.”

Meanwhile, some communities have added a controversial prevention effort: Deer kills. Because a deer can harbor hundreds of ticks, some studies and experiments show killing deer can reduce tick-borne diseases in people. Dover, Sudbury and other communities have allowed bow-and-arrow hunting on some town lands for several years; Westborough began allowing it two years ago.

The Environmental Bond bill passed last year required the state to develop a plan to safely and humanely cull deer where their numbers have risen too high, such as in the Blue Hills Reservation outside Boston.

“We have a real threat to public health,’’ said Sen. Brian A. Joyce, a Milton Democrat, who proposed the language in the bond bill.

READ MORE FROM NECIR: FDA to regulate Lyme, other diagnostic tests

A spokesman for the state Department of Conservation and Recreation said state officials are developing recommendations for the Blue Hills herd and will seek the public’s input before any formal plan is adopted.

But others, including some academics, say it is not clear fewer deer will translate into fewer cases of Lyme, in part because ticks get transported on so many other animals.

One of the only points of agreement for most people involved in the Lyme – and deer – debate is that people should personally protect themselves. Experts also warn that while pest-control companies are increasingly offering tick control, such as spraying yard perimeters, they need to beware of claims, especially of all-natural products.

While Nootkatone, a bio-active natural component of Alaskan yellow cedar oil, has been shown to kill ticks in high numbers, it is currently quite expensive to produce, according to Tom Mather, a University of Rhode Island professor and tick expert who runs www.tickencounter.org, a website dedicated to tick prevention. Many pest control companies offer non-yellow cedar products that do not work well against ticks, said Mather, who has tested some of the products’ main ingredients. It turns out that red cedar is just not the same as yellow cedar.

“We found no tick-killing effect using two different red cedar products. People need to be warned. There are so many formulations of botanical oils but so few have actually been tested against ticks,” Mather said.

And it may be an important year to work on tick protection. According to Jim Dill, a pest management specialist at the University of Maine, the extreme cold probably didn’t kill many ticks this winter because “most of them were three feet under…warm and well-insulated” by the snow, he said.

Beth Daley is a reporter at the New England Center for Investigative Reporting, an independent, nonprofit news center based at Boston University and WGBH News. She can be reached bdaley@bu.edu. Follow her on Twitter at @bethbdaley.

To get more great journalism from NECIR, follow us on Twitter and Facebook, or sign up for our email list.