One-on-one with Mass. Senate President Karen Spilka

Karen Spilka sat down with NBC10 Boston’s Matt Prichard to discuss ballot questions, the current legislative session, reelection and more

Karen Spilka sat down with NBC10 Boston’s Matt Prichard to discuss ballot questions, the current legislative session, reelection and more

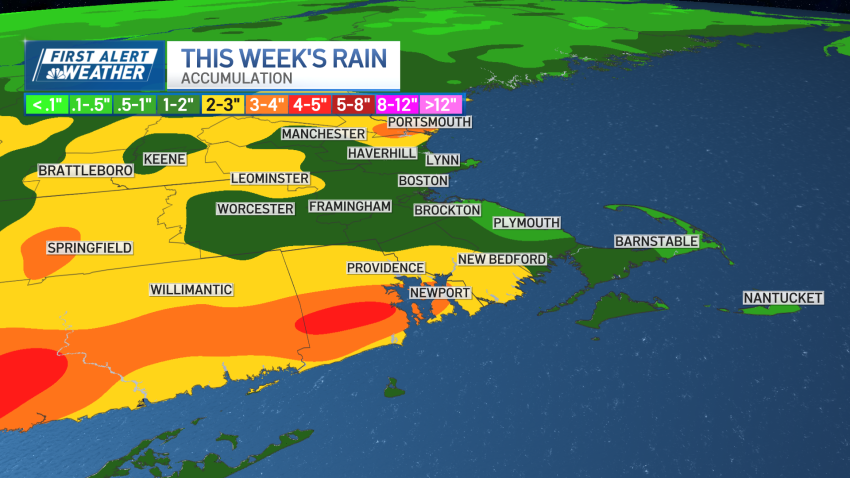

After Saturday storms across the region, Sunday stays unsettled with isolated showers across southern New England, but it’s not a total washout. You’ll want the umbrella nearby just in case.

Boston Red Sox first baseman Triston Casas suffered a ruptured tendon in his left knee and is out for the remainder of the season, the team said on Saturday.

After a rampage involving a carjacking and pedestrian hit-and-run in Lowell, a man was arrested in a culvert off I-495 miles across Mass. Friday night, authorities say.

While the official Run for the Roses captivated crowds at Churchill Downs, the spirit – and fashion – of the Kentucky Derby galloped into Boston’s Seaport on Saturday.

With a storm system causing heavy winds in Boston and across New England Saturday, thousands of people were without power.

An elderly man died when his pickup truck was hit by an MBTA train in Cohasset, Massachusetts, on Saturday, police said.

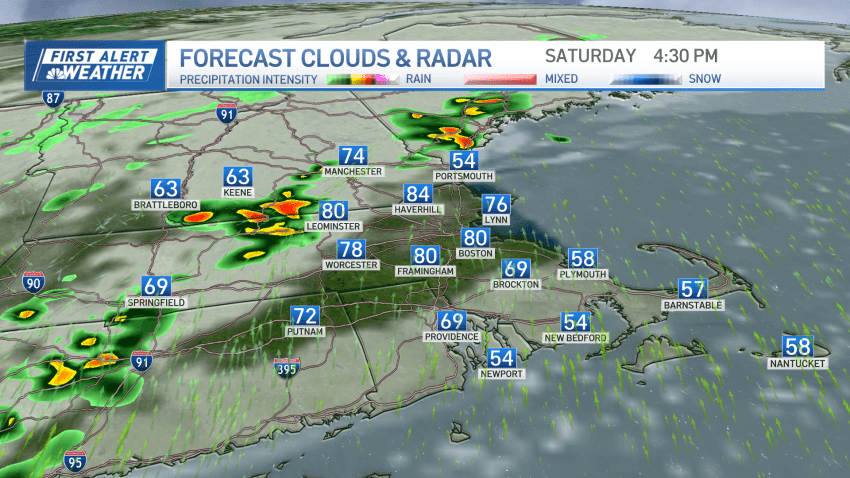

More severe thunderstorms will develop Saturday afternoon and will head towards Boston by the evening

A man was seriously hurt when his motorcycle crashed Friday evening in Tewksbury, Massachusetts, Friday evening, police said.

Celtics wing Jaylen Brown could play a crucial role in containing Knicks superstar Jalen Brunson during this second-round series, writes Chris Forsberg.

A drunken driver was arrested after a crash into a Massachusetts State Police cruiser on Interstate 93 in Milton early Saturday morning, officials said.