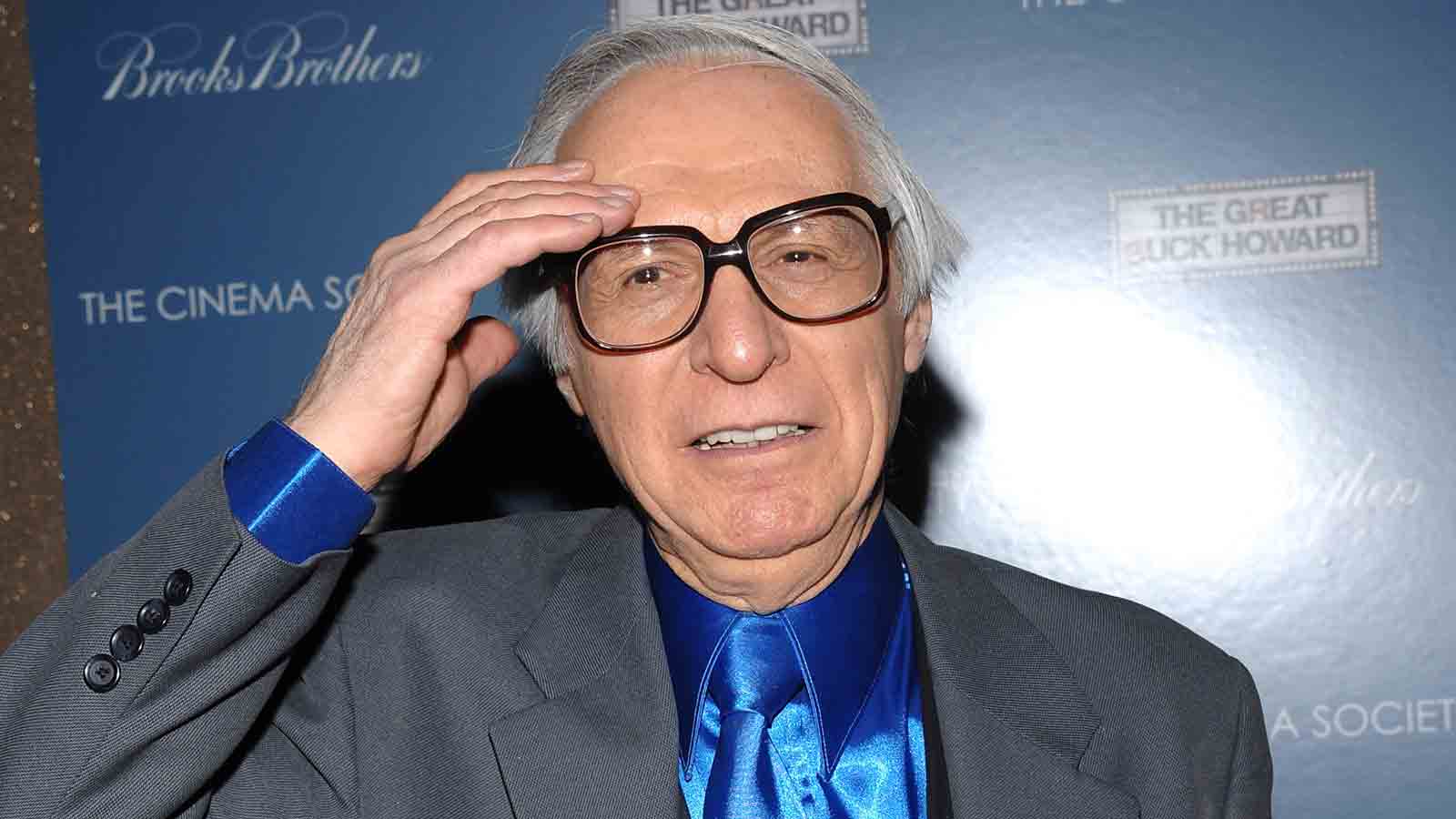

James Earl Jones, who overcame racial prejudice and a severe stutter to become a celebrated icon of stage and screen — eventually lending his deep, commanding voice to CNN, “The Lion King” and Darth Vader — has died. He was 93.

His agent, Barry McPherson, confirmed Jones died Monday morning at home in New York's Hudson Valley region. The cause was not immediately clear.

The pioneering Jones, who in 1965 became one of the first African American actors in a continuing role on a daytime drama (“As the World Turns”) and worked deep into his 80s, won two Emmys, a Golden Globe, two Tony Awards, a Grammy, the National Medal of Arts and the Kennedy Center Honors. He was also given an honorary Oscar and a special Tony for lifetime achievement. In 2022, a Broadway theater was renamed in his honor.

He cut an elegant figure late in life, with a wry sense of humor and a ferocious work habit. In 2015, he arrived at rehearsals for a Broadway run of “The Gin Game” having already memorized the play and with notebooks filled with comments from the creative team. He said he was always in service of the work.

“The need to storytell has always been with us,” he told The Associated Press then. “I think it first happened around campfires when the man came home and told his family he got the bear, the bear didn't get him."

Jones created such memorable film roles as the reclusive writer coaxed back into the spotlight in “Field of Dreams,” the boxer Jack Johnson in the stage and screen hit “The Great White Hope,” the writer Alex Haley in “Roots: The Next Generation” and a South African minister in “Cry, the Beloved Country.”

He was also a sought-after voice actor, expressing the villainy of Darth Vader (“No, I am your father,” commonly misremembered as “Luke, I am your father”), as well as the benign dignity of King Mufasa in both the 1994 and 2019 versions of Disney's “The Lion King” and announcing “This is CNN” during station breaks. He won a 1977 Grammy for his performance on the “Great American Documents” audiobook.

Entertainment News

“If you were an actor or aspired to be an actor, if you pounded the payment in these streets looks for jobs, one of the standards we always had was to be a James Earl Jones,” Samuel L. Jackson once said.

Some of his other films include “Dr. Strangelove,” “The Greatest” (with Muhammad Ali), “Conan the Barbarian,” “Three Fugitives” and playing an admiral in three blockbuster Tom Clancy adaptations — “The Hunt for Red October,” “Patriot Games” and “Clear and Present Danger.” In a rare romantic comedy, “Claudine,” Jones had an onscreen love affair with Diahann Carroll.

LeVar Burton, who starred alongside Jones in the TV movie “Guyana Tragedy: The Story of Jim Jones,” paid tribute on X, writing, "There will never be another of his particular combination of graces.”

Jones made his Broadway debut in 1958’s “Sunrise At Campobello” and would win his two Tony Awards for “The Great White Hope” (1969) and “Fences” (1987). He also was nominated for “On Golden Pond” (2005) and “Gore Vidal’s The Best Man” (2012). He was celebrated for his command of Shakespeare and Athol Fugard alike. More recent Broadway appearances include “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” “Driving Miss Daisy,” “The Iceman Cometh,” and “You Can’t Take It With You.”

As a rising stage and television actor, he performed with the New York Shakespeare Festival Theater in “Othello,” “Macbeth” and “King Lear” and in off-Broadway plays.

Jones was born by the light of an oil lamp in a shack in Arkabutla, Mississippi, on Jan. 17, 1931. His father, Robert Earl Jones, had deserted his wife before the baby's arrival to pursue life as a boxer and, later, an actor.

When Jones was 6, his mother took him to her parents' farm near Manistee, Michigan. His grandparents adopted the boy and raised him.

“A world ended for me, the safe world of childhood,” Jones wrote in his autobiography, “Voices and Silences.” “The move from Mississippi to Michigan was supposed to be a glorious event. For me it was a heartbreak, and not long after, I began to stutter.”

Too embarrassed to speak, he remained virtually mute for years, communicating with teachers and fellow students with handwritten notes. A sympathetic high school teacher, Donald Crouch, learned that the boy wrote poetry, and demanded that Jones read one of his poems aloud in class. He did so faultlessly.

Teacher and student worked together to restore the boy’s normal speech. “I could not get enough of speaking, debating, orating — acting,” he recalled in his book.

At the University of Michigan, he failed a pre-med exam and switched to drama, also playing four seasons of basketball. He served in the Army from 1953 to 1955.

In New York, he moved in with his father and enrolled with the American Theater Wing program for young actors. Father and son waxed floors to support themselves while looking for acting jobs.

True stardom came suddenly in 1970 with “The Great White Hope.” Howard Sackler’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Broadway play depicted the struggles of Jack Johnson, the first Black heavyweight boxing champion, amid the racism of early 20th-century America. In 1972, Jones repeated his role in the movie version and was nominated for an Academy Award as best actor.

Jones’ two wives were also actors. He married Julienne Marie Hendricks in 1967. After their divorce, he married Cecilia Hart, best known for her role as Stacey Erickson in the CBS police drama “Paris,” in 1982. (She died in 2016.) They had a son, Flynn Earl, born in 1983.

In 2022, the Cort Theatre on Broadway was renamed after Jones, with a ceremony that included Norm Lewis singing “Go the Distance,” Brian Stokes Mitchell singing “Make Them Hear You” and words from Mayor Eric Adams, Samuel L. Jackson and LaTanya Richardson Jackson.

“You can’t think of an artist that has served America more,” director Kenny Leon told the AP. “It’s like it seems like a small act, but it’s a huge action. It’s something we can look up and see that’s tangible.”

Citing his stutter as one of the reasons he wasn’t a political activist, Jones nonetheless hoped his art could change minds.

“I realized early on, from people like Athol Fugard, that you cannot change anybody’s mind, no matter what you do,” he told the AP. “As a preacher, as a scholar, you cannot change their mind. But you can change the way they feel.”