The headlines shocked the country in June when multiple people were indicted for allegedly stealing human remains from the Harvard Medical School morgue and sending them to buyers across the country.

The case put a spotlight on the online human remains trade and the laws surrounding the buying and selling of body parts in the United States. NBC10 Boston spoke with experts around the country to break down this legal and ethical debate.

“This is a much larger story than most people understand or can really wrap their minds around,” said Sam Redman, a history professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the author of “Bone Rooms,” which details the history of the collection and showcasing human remains.

Bone rooms — which Redman describes as typically large, cool, dry rooms with a distinct odor lying behind a wooden door with cabinets and drawers holding various remains – hold the key to hundreds of years of history in museums across the world.

“People very rarely know or fully comprehend that there are more than half a million sets of human remains in the United States and probably another half a million sets of native remains that are held by museums in Europe,” he said.

When asked about the allegations about the Harvard morgue, Redman says what’s surprising is how similar they are to the history of fascination about human remains in the United States dating back to the 1800s.

“I find myself continually shocked and appalled, and then another part of me also finds it not surprising at all,” Redman said of the Harvard allegations. “It fits quite neatly into this longer tradition of collection and exploitation of the dead that has happened in our country since the 18th and 19th centuries.”

WHAT HAPPENED AT HARVARD

Multiple people were indicted in June after being accused of stealing and selling body parts from Harvard Medical School’s morgue from 2018-2023, according to federal prosecutors.

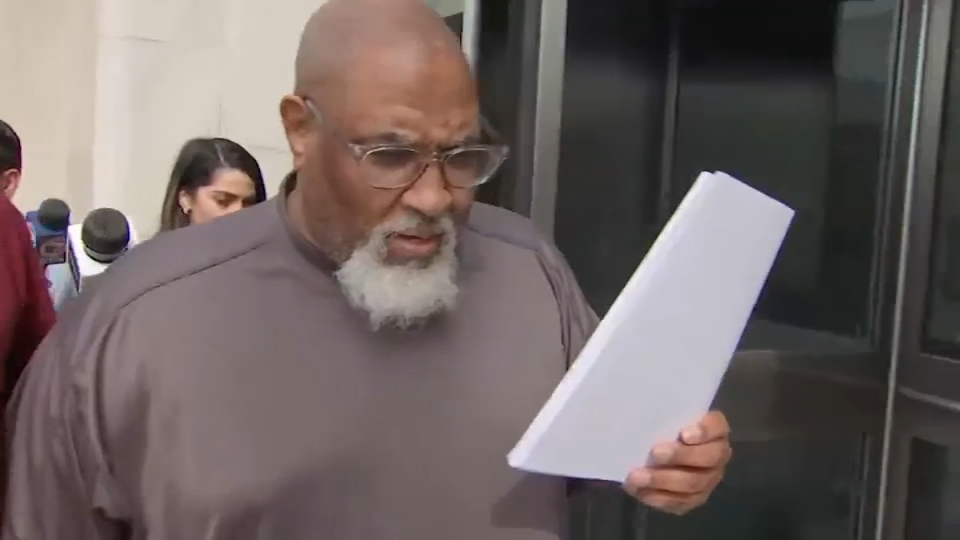

Cedric Lodge, the 55-year-old manager of the Harvard Anatomical Gift Program’s morgue, is accused of letting buyers come into the morgue to select which remains they wanted to buy, stealing those parts of donated cadavers, taking them home with him to New Hampshire and shipping them to buyers in the mail, prosecutors said.

Lodge was fired in May and the Harvard deans wrote an emotional public letter, titled “An abhorrent betrayal,” explaining the indictment and apologizing for the pain this would cause the community and the families of those affected

Cadavers were donated to the Anatomical Gift Program to be used for research and later returned to the families or buried in a cemetery in Tewksbury, Massachusetts, according to the indictment, but officials say up to 400 body parts were stolen and sold from the morgue.

Along with Lodge, six others were indicted in federal court for their alleged roles in the Harvard morgue scandal: Denise Lodge (Cedric Lodge’s wife), 63 of Goffstown, New Hampshire; Katrina Maclean, 44, of Salem, Massachusetts; Joshua Taylor, 46, of West Lawn, Pennsylvania; Mathew Lampi, 52, of East Bethel, Minnesota; and Jeremy Pauley, 41, of Thompson, Pennsylvania. Candace Chapman-Scott, 36, of Little Rock, Arkansas, has also been indicted.

The report says that between 2018-2021, Taylor sent 39 electronic payments for stolen human remains to Denise Lodge through PayPal, totaling about $37,000. Two of those payments had memos that read, “head number 7” and “'braiiiiiins.”

Lampi allegedly exchanged more than $100,000 with Pauley as they bought and sold items made from human remains.

Maclean ran a store called Kat’s Creepy Creations in Peabody, Massachusetts. In 2020, Maclean allegedly paid $600 to Cedric Lodge for two desiccated faces from the Harvard morgue. On another occasion, she allegedly shipped human skin to Pauley so he could tan it and turn it into leather, according to the report.

A Facebook post from April 3 on Pauley’s public page also shows two silver cufflinks with human skin and hair inlay. Pauley described it as a “Personal project.”

Pauley was arrested in Pennsylvania last year and is accused of buying stolen remains from Scott, who allegedly stole remains from her employer at a mortuary and crematorium in Little Rock, Arkansas, according to the U.S. District Attorney’s office. She is accused of stealing parts of cadavers as well as two stillborn babies that were meant to be cremated and returned to their families.

Last week, Pauley pleaded guilty to conspiracy and interstate transportation of stolen property. Pauley admitted to knowingly buying and selling stolen human remains, according to federal prosecutors in Pennsylvania.

The other people accused in the case are awaiting their trials.

Since the indictments, multiple class-action lawsuits have been filed by families who had loved ones affected by the mishandling of human remains at the Harvard morgue. Harvard has told NBC10 Boston it does not comment on pending litigation.

But it has asked a panel of outside experts to review its body donation program. The report was expected to be released by the end of summer, but was recently delayed until October.

IT'S HAPPENED BEFORE

The Harvard morgue scandal is not the first time a university’s morgue was caught for stealing and selling cadavers.

In 2004, Henry Reid, the former director of the University of California, Los Angeles’s Willed Body Program and a former employee of the morgue, Ernest Nelson, were convicted in a conspiracy case to buy and sell remains for personal profit.

Reid pled guilty and was sentenced to four years and four months in state prison and Nelson was sentenced to ten years after a jury found him guilty on eight counts, including tax evasion and grand theft.

THE LAW

“It’s not a black market, it’s sort of a grey market,” Tanya Marsh explains of the human remains trade.

Marsh is a professor at the Wake Forest University School of Law and teaches a course on funeral and cemetery law. She also wrote a book titled, “The Law of Human Remains.”

“In 42 states it’s completely legal to sell human remains in brick-and-mortar stores,” she said. “There is no federal law specifically stating that selling human remains is illegal.”

Marsh said there are only eight states – Florida, Georgia, Massachusetts, Missouri, New Hampshire, South Carolina, Texas and Virginia - where it is broadly illegal to buy and sell human remains, but the penalties are low.

In Massachusetts, the law states, “Whoever buys or sells, or has in his possession for the purpose of buying, selling or trafficking in, the dead body of a human being shall be punished by a fine of not less than fifty nor more than one thousand dollars or by imprisonment for not less than three months nor more than two and one half years.”

The Harvard case crosses multiple borders with a variety of state laws (Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, to name a few) and the penalties for buying and selling of stolen goods are much higher than the state laws specifically targeting the sale of body parts.

As there is no federal law regarding human remains, those indicted were charged with “conspiracy” and “interstate transport of stolen goods.”

If convicted, those indicted in the case could face up to 15 years in prison, prosecutors said.

Marsh points out that the laws of human remains have been created episodically.

This often occurs when the public learns of a disturbing event and a series of laws are proposed to prevent that particular thing from happening again – such as grave robbing or other laws specifically around remains that have already been buried.

Marsh said the issue with state statute is the lack of a cohesive set of laws to address the buying and selling of human remains.

Particularly in the Harvard morgue scandal, she feels that it’s best to wait and see how this indictment plays out before proposing new legislation.

“If the prosecution is successful under the existing statute, then you don’t really need to have a new specific statute that just deals with human remains,” she said.

While there is no broad federal law pertaining to human remains, there is one directly related to Native American remains.

In November 1990, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was enacted to provide repatriation and disposition of certain Native American human remains and sacred objects.

The law came into being after years of Native American lobbying due to the extensive collection and unfair treatment of remains in museums and private collections.

“Most people would be shocked to know that only 30% of human remains have gone home since the 1990 passage of that law,” Redman says.

He explained that curators and scholars at institutions collecting Native American remains could claim that they were culturally unidentifiable, creating a loophole around returning remains and paying restitution. If they didn’t know the community in which the remains were from, who would they pay? And where would they return it?

THE ONLINE TRADE IN REMAINS

“The trade in human remains matters because there are these historical wrongs that have happened that ancestors have been taken from their communities,” Shawn Graham, a professor of digital humanities in the history department at Carleton University, says. “Those ancestors need to be returned.”

Graham has been studying the online human remains trade for over five years. Many of the bodies he has seen emerge are from the needs of medical schools in North America and a majority of those bodies are from poor non-white populations.

In 2015, Graham met osteoarchaeologist Damien Huffer at an archaeology conference. With Huffer’s background in studying human skeletal remains and Graham’s background in digital methods, they realized they could combine forces to study the markets and how the human remains trade was evolving.

Together they work on “The Bone Trade Project,” which looks at how people are using social media to buy and sell human remains through text analysis. They watch comments on social media platforms to determine how people talk about the remains, if people are treating them as objects and trinkets, for educational value or other motives. In more recent studies, they are now looking at how the images have been composed and shared.

They also came out this month with a new book “These Were People Once: The Online Trade in Human Remains, and Why It Matters,” revealing their findings.

The goal of their work is to find the true motivation of those involved in the trade – why are people doing this?

“Across the board the motivation is just control -- control the dead,” says Huffer, a resident of Brisbane, Australia. “Being able to own someone else.”

“There’s this othering and treatment of the dead as curios,” Graham said, explaining that people turn remains into various necklaces, chandeliers, pendants or other artworks. “What’s coming through all of these is this kind of fundamental lack of dignity or respect.”

Prior to the 2010s, Graham and Huffer say the human remains trade was booming mostly on Etsy and eBay. But in 2012, Etsy added human remains to their list of prohibited items to sell (human hair, teeth and fingernails are allowed) and in 2016, eBay followed suit, prohibiting bodies, body parts or products made from human body parts from being sold on their site. Their only exception is human scalp hair.

Graham and Huffer name Instagram and Facebook as the two players they have their eyes on the most. They use data scraping to review comments that come with posts to see what people are talking about in regard to the items for sale. The researchers also scrape smaller country- or language-specific e-commerce platforms.

Meta, the company that owns Instagram and Facebook, issued a policy stating that any ads or listings “may not promote the buying or selling of human body parts or fluids.” The social media conglomerate also has rules to remove harmful content from their platforms including organ sales.

But Graham and Huffer insist the trade continues on.

“Social media platforms are notoriously bad for moderation of all sorts of different things,” Graham explains.

Huffer says that there are loopholes to the bans, suggesting that dealers can post items and not list them for sale, but indicate they could be available for purchase if directly contacted. Others could use private groups or messaging to discuss sales further.

“I don’t think it’ll ever go away,” Huffer says about the online trade. “I just think it’ll keep shifting.”

Huffer also expressed worry that if enough people report the posts and social media giants delete them, it could destroy the only evidence researchers and law enforcement may have for putting a stop to it.

A CALL TO ACTION

“The cautionary tale of ‘this happened at Harvard’ has terrified medical schools across the country,” Marsh said. “This has been a really disturbing wake-up call.”

Marsh also expressed concern for the future of body donation programs at universities, stating she hopes this will not deter families from donating to science in the future.

‘There is still value in donating to science, in trusting most of these institutions that would handle the body donation process,” Huffer agreed.

In addition to the wake-up call to institutions, the National Funeral Directors Association introduced the “Consensual Donation and Research Integrity Act” also known as the “Body Broker Bill.”

According to the NFDA’s website, the bill would create “a clear chain of custody for each human body or body part; ensures shipments of human bodies and body parts are properly labeled and packaged; and ensures the respectful and proper disposition of donated bodies and body parts. Additionally, the CDRI Act establishes penalties for violations.”

And while Marsh feels it is important to wait to see how the prosecution pans out before introducing new legislation, Redman asks for a call to action:

“I think that this situation just screams out for added investigation by lawmakers and policymakers to think more deeply about the way in which we treat the dead,” he said.