Tiara Simmons at The Pike, a shopping and amusement complex in Long Beach, Calif., she enjoys visiting with her family.

This story is part of CNBC Make It's Millennial Money series, which details how people around the world earn, spend and save their money.

Tiara Simmons understands — maybe better than most people — that money often equals access.

The 39-year-old is a below-the-knee amputee and uses an electric wheelchair full-time. Though she's been disabled for nearly her entire life, she "wasn't raised to think of myself as being disabled." Like any other child, she dreamt of a future without limitations and says she didn't really encounter ableism until after college.

A hefty settlement allowed Simmons to experience the kind of life you can live when you're not worried about money, but it didn't last. Now she earns roughly $26,000 per year between her job as a law clerk and social media marketing side hustle.

She lives with her husband, who works part-time, her 3-year-old son and their chihuahua in a one-bedroom apartment in Long Beach, California. With a median income of around $84,000 a year, California isn't known for its affordability. But more affordable places aren't always more accessible, Simmons says.

She was recently sworn-in as an attorney, but isn't doing it for the money — even if it would make parts of her life easier. Rather, she hopes to one day become a public defender helping clients without the means for legal representation.

"I'm not rolling in the dough right now and I probably will never be," Simmons tells CNBC Make It. "But as long as I can survive and as long as I'm doing what I think is my mission in life, I'm OK."

Money Report

How she spends her money

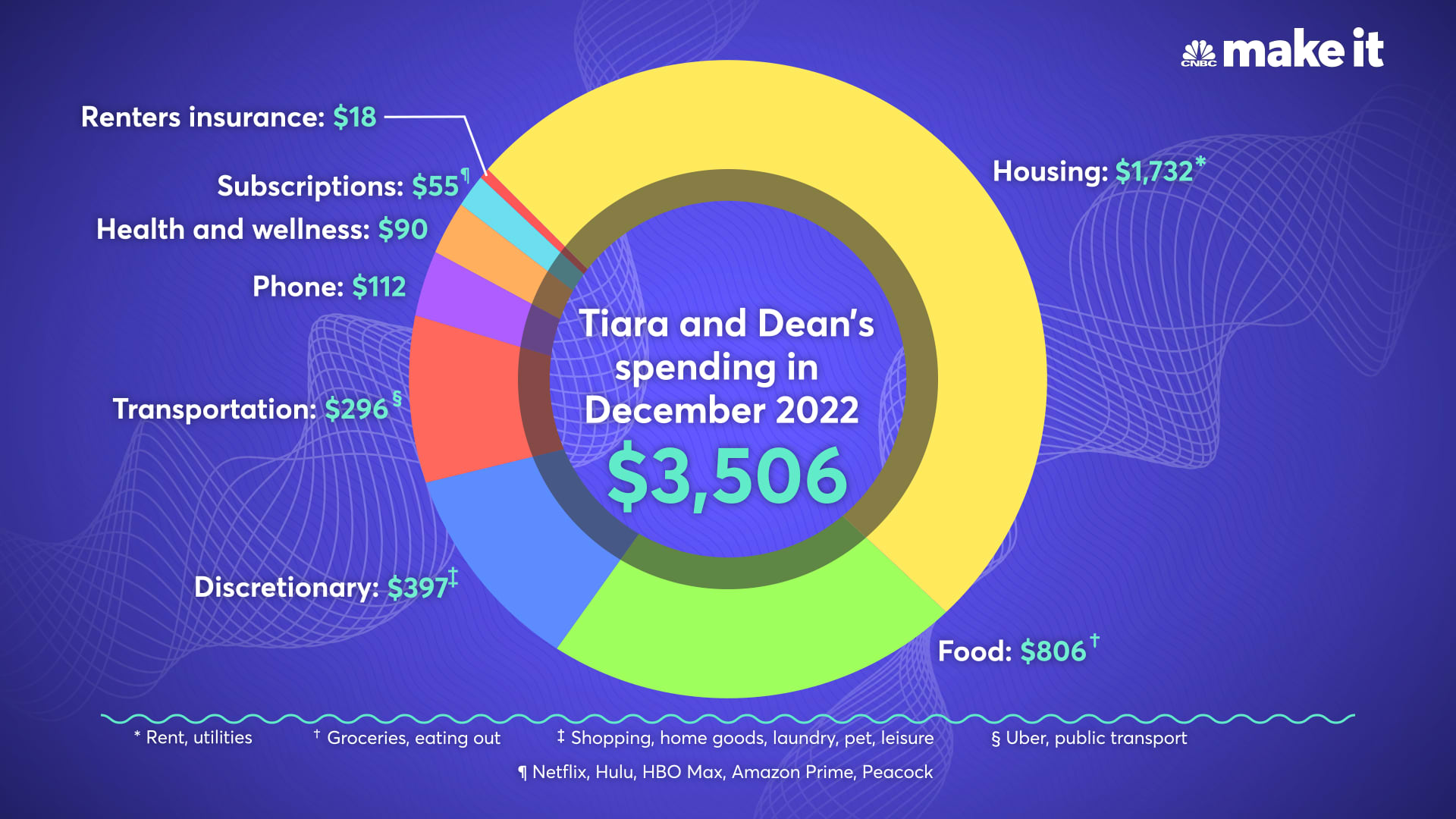

Here's a look at how Simmons and her husband, Dean, spent their money in December 2022.

- Housing and utilities: $1,705 for rent, Wi-Fi, sewage and waste management, water, gas and electric

- Food: $806 on groceries and dining out

- Discretionary: $397 on laundry, diapers, home goods and entertainment/leisure

- Transportation: $296 for Uber and public transportation

- Phone: $112 for two phone lines

- Health and wellness: $90 for various over-the-counter medications and supplies

- Subscriptions: $55 for Netflix, Hulu, HBO max, Amazon Prime and Peacock

- Renters insurance: $18. She receives state-sponsored health care for free

- Debt repayment: $0 while her student loans are on disability discharge

Simmons and her husband use a joint account to take care of bills and expenses. The family receives SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) benefits to help with groceries. They don't have much room for savings, but Simmons was able to open a retirement account recently, though she doesn't currently make regular contributions.

Simmons and her husband's work schedules, along with occasional help from friends and family, allow them to avoid paying for outside child care.

At times, she says, they've been able to sock away a little money as emergency savings, but one way or another, necessities kept coming up. She was saving up to pay for her bar exam, but that money wound up going toward moving costs when she had to move to a more affordable apartment.

Sometimes she faces obstacles to working that able-bodied people wouldn't have, which causes her to lose income.

"I don't spend a lot of money, if any, out of pocket on my wheelchair," Simmons says. "The only expense would be the money that I don't make because of wheelchair repairs. I have to miss work sometimes. Besides just spending money, we lose the opportunity to make money."

'It opened up the world for me, using my wheelchair'

A New York native, Simmons wasn't born with her disability. As an infant, she developed a treatable blood infection that wasn't properly taken care of.

"From what I was told, the doctors just dismissed my mother like, 'she's colicky, she's fine,'" Simmons says.

The infection turned to gangrene and resulted in the amputation of both Simmons' legs. She received prosthetic legs when she was 4, which allowed her to walk for the first time, and continued to use prosthetics growing up. She switched to using a wheelchair full-time after she finished college.

"There's this belief that walking is always easier, but for me it wasn't because it was 20-pound prosthetic legs and crutches," she says. "It became easier to just use my wheelchair — it opened up the world for me, using my wheelchair."

A lawsuit filed against the hospital where Simmons was born resulted in a $2.5 million settlement in her favor, she says. (CNBC Make It was not able to independently confirm this number.) But she didn't know about the money until she was entering her senior year of high school, when her guardian was required to inform her.

The settlement allowed Simmons to graduate debt-free from The College of New Rochelle in New York with a bachelor's degree in psychology, buy a home at 17 and travel whenever she wanted. She spent freely, but not carelessly — she knew the money could run out fast.

She moved from New York to California in 2010, partly because the milder climate is easier on her wheelchair, but also because the state's earthquakes have led to updated buildings with better accessibility than states with older infrastructure.

'All your money is gone'

Life on the West Coast was going well for Simmons. The settlement money allowed her to stay on top of bills and expenses with relative ease, sometimes even paying two months' rent in advance "just to make sure that I didn't have to worry about anything."

Though she had access to the funds, Simmons allowed a family member to help her manage the settlement money since she was young and still learning how to use it herself, she says. But one day, she was told the money was gone.

"I woke up that morning knowing that I could pay my bills, knowing that I would have no problem paying rent," Simmons says. "And by the end of that particular day, I had gotten off the phone with a family member who told me, 'all of your money is gone.'"

The only explanation she ever received for its disappearance was that there was a "bad investment."

Moving forward

Though the settlement money allowed Simmons to de-prioritize finding a job, she always wanted to work. Learning the money was gone sent her into "full panic mode" to find a source of income.

"People don't tend to hire disabled people and I can't just go work at ABC minimum wage job or whatever," she says. "I was willing, but there wasn't much that I could do considering my type of disability."

Simmons had just begun applying to law schools when she found out her settlement money was gone. She had already expected to take on some student debt, but without the extra help she ended up with over $400,000 in loans.

Despite the debt, Simmons stayed confident in her choice to attend law school and become an attorney. "A lot of that goal was fueled by knowing that if I can become a lawyer, I can work for myself," she says.

For Simmons, working for herself isn't just about entrepreneurship — it's about access. One reason it's expensive to have disability, she says, is because in many instances — housing, transportation, clothes — her options are so limited she can't always take the more affordable one.

"I don't have a lot of options due to disability as far as where I can live, where I can go, where I can work," Simmons says. "Even if there was this amazing job opportunity out there for me, I would have to turn it down if it's someplace that I cannot get to on public transportation because taxis and even Ubers, they're not options for me."

Another reason Simmons isn't aiming to earn a huge salary as a lawyer: Earning too much would reinstate her student loan payments. While she's not currently making payments, her disability discharge is on the condition that she continues earning below the federal poverty line.

"It's very stressful knowing that if I make enough money to live and take care of myself and my son and my family, that all of that money will be reinstated and then I'll have to pay it back."

Her mission in life

As she works toward her goal of becoming a public defender, Simmons is already aiming to help those who can't afford legal representation or who need physically accessible services.

She opened her virtual law firm online not only so she can work from home, but so her clients can reach her wherever they are. Right now, she's focused on learning everything she can through her current job and growing her client list through her virtual firm.

Simmons says one commonly held misconception about disabled people is that they're lazy.

"A lot of us cannot subscribe to the hustle culture that has become our society, and it's not because we're lazy, it's because we're disabled," she says. "And that's something that I repeat very often — disabled, not lazy."

Though she says it's tough, Simmons works tirelessly to support her family and grow her career. She wants to be able to build generational wealth for her son and teach him the money values she didn't have growing up.

"I want [my son] to have the same experience of just togetherness and just love that we felt growing up," she says. "I want him to understand — when it's time — the value of money and how our lives are kind of ruled by money and how much you have. Money doesn't buy happiness, but money does buy you a roof over your head."

What's your budget breakdown? Share your story with us for a chance to be featured in a future installment.

Sign up now: Get smarter about your money and career with our weekly newsletter

Don't miss: New York City, Las Vegas are among the 10 most accessible cities in the world for people with disabilities