President Joe Biden appealed to world leaders at a COVID-19 summit Thursday to reenergize a lagging international commitment to attacking the virus as he led the U.S. in marking the “tragic milestone” of 1 million deaths in America. He ordered flags lowered to half-staff and warned against complacency around the globe.

“This pandemic isn’t over,” Biden declared at the second global pandemic summit. He spoke solemnly of the once-unthinkable U.S. toll: “1 million empty chairs around the family dinner table.”

The coronavirus has killed over 1 million people in the U.S. and more than 6.2 million people globally, according to figures complied by NBC News.

The president called on Congress to urgently provide billions of dollars more for testing, vaccines and treatments, something lawmakers have been unwilling to deliver so far.

The lack of funding — Biden has requested another $22.5 billion of what he calls critically needed money — is a reflection of faltering resolve at home that jeopardizes the global response to the pandemic.

Eight months after he used the first such summit to announce an ambitious pledge to donate 1.2 billion vaccine doses to the world, the urgency of the U.S. and other nations to respond has waned.

Momentum on vaccinations and treatments has faded even as new, more infectious variants rise and billions across the globe remain unprotected. Congress has refused to meet Biden’s request to provide another $22.5 billion in what he has called critically needed aid funding.

Biden addressed the opening of the virtual summit Thursday morning with recorded remarks and made the case that tackling COVID-19 “must remain an international priority.” The U.S. is co-hosting the summit along with Germany, Indonesia, Senegal and Belize.

“This summit is an opportunity to renew our efforts to keep our foot on the gas when it comes to getting this pandemic under control and preventing future health crises,” Biden said.

More COVID-19 Coverage

The U.S. has shipped nearly 540 million vaccine doses to more than 110 countries and territories, according to the State Department — by far more than any other donor nation.

The leaders announced about $3 billion in new commitments to fight the virus, along with a host of new programs meant to boost access to vaccines and treatments around the world. But that was a far more modest outcome than at last year’s meeting.

After the delivery of more than 1 billion vaccines to the developing world, the problem is no longer that there aren’t enough shots, but a lack of logistical support to get doses into arms. According to government data, more than 680 million donated vaccine doses have been left unused in developing countries because they were set to expire soon and couldn’t be administered quickly enough. As of March, 32 poorer countries had used fewer than half of the COVID-19 vaccines they were sent.

U.S. assistance to promote and facilitate vaccinations overseas dried up earlier this year, and Biden has requested about $5 billion for the effort through the rest of the year.

“We have tens of millions of unclaimed doses because countries lack the resources to build out their cold chains, which basically is the refrigeration systems; to fight disinformation; and to hire vaccinators,” White House press secretary Jen Psaki said this week. She added that the summit is “going to be an opportunity to elevate the fact that we need additional funding to continue to be a part of this effort around the world.”

“We’re going to continue to fight for more funding here,” Psaki said. “But we will continue to press other countries to do more to help the world make progress as well.”

Congress has balked at the price tag for COVID-19 relief and has thus far refused to take up the package because of political opposition to the impending end of pandemic-era migration restrictions at the U.S.-Mexico border. Even after a consensus for virus funding briefly emerged in March, lawmakers decided to strip out the global aid funding and solely focus the assistance on shoring up U.S. supplies of vaccine booster shots and therapeutics.

Biden has warned that without Congress acting, the U.S. could lose out on access to the next generation of vaccines and treatments, and that the nation won't have enough supply of booster doses or the antiviral drug Paxlovid for later this year. He's also sounding the alarm that more variants will spring up if the U.S. and the world don't do more to contain the virus globally.

“To beat the pandemic here, we need to beat it everywhere,” Biden said last September during the first global summit.

In an interview Thursday with The Associated Press, White House COVID-19 coordinator Dr. Ashish Jha pressed the need for the U.S. to fund global vaccination efforts as a way to protect Americans at home, warning that strains like delta and omicron first sprang up overseas.

“All of these variants were first identified outside of the United States," he said. "If the goal is to protect the American people, we have got to make sure the world is vaccinated. There’s just no domestic-only approach here.”

Demand for COVID-19 vaccines has dropped in some countries as infections and deaths have declined globally in recent months, particularly as the omicron variant has proved to be less severe than earlier versions of the disease. For the first time since it was created, the U.N.-backed COVAX effort has “enough supply to enable countries to meet their national vaccination targets,” according to vaccines alliance Gavi CEO Dr. Seth Berkley, which fronts COVAX.

Still, despite more than 65% of the world’s population receiving at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose, fewer than 16% of people in poor countries have been immunized. It is highly unlikely countries will hit the World Health Organization target of vaccinating 70% of all people by June.

In countries including Cameroon, Uganda and the Ivory Coast, officials have struggled to get enough refrigerators to transport vaccines, send enough syringes for mass campaigns and get enough health workers to inject the shots. Experts also point out that more than half of the health workers needed to administer the vaccines in poorer countries are either underpaid or not paid at all.

Donating more vaccines, critics say, would miss the point entirely.

“It’s like donating a bunch of fire trucks to countries that are on fire, but they have no water,” said Ritu Sharma, a vice president at the charity CARE, which has helped immunize people in more than 30 countries, including India, South Sudan and Bangladesh.

“We can’t be giving countries all these vaccines but no way to use them,” she said, adding that the same infrastructure that got the shots administered in the U.S. is now needed elsewhere. “We had to tackle this problem in the U.S., so why are we not now using that knowledge to get vaccines into the people who need them most?”

Sharma said greater investment was needed to counter vaccine hesitancy in developing countries where there are entrenched beliefs about the potential dangers of Western-made medicines.

“Leaders must agree to pursue a coherent strategy to end the pandemic instead of a fragmented approach that will extend the lifespan of this crisis,” said Gayle Smith, CEO of The ONE Campaign.

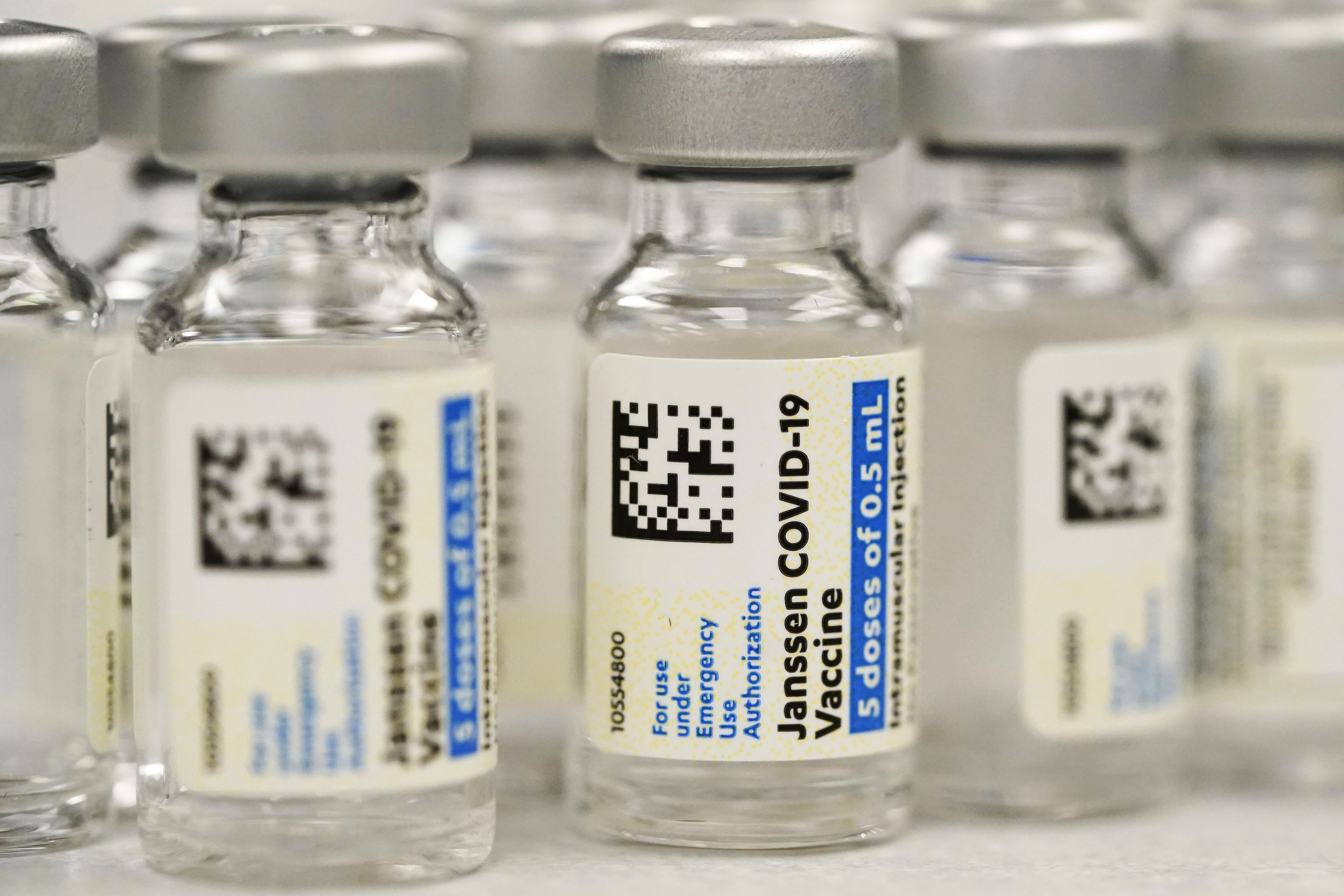

Gavi’s Berkley also said that countries are increasingly asking for the pricier messenger RNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna, which are not as easily available as the AstraZeneca vaccine, which made up the bulk of COVAX’s supply last year.

Variants like delta and omicron have led many countries to switch to mRNA vaccines, which seem to provide more protection and are in greater demand globally than traditionally made vaccines like those from China and Russia.

Cheng reported from London. AP writer Chris Megerian contributed.