The state board of education voted Monday to raise the minimum score that this year's incoming freshman class and at least the four classes that follow will have to attain on the MCAS test in order to graduate high school, a controversial decision that was blasted by teachers union officials and a handful of lawmakers.

The Board of Elementary and Secondary Education accepted Commissioner Jeff Riley's recommendation to update MCAS regulations and the competency determination that would establish a new passing standard for English language arts, mathematics, and science and technology/engineering for the classes of 2026 through 2029. The board also adopted an amendment to Riley's plan proposed by member Martin West extending the new requirements to the class of 2030 and providing a starting point for the thresholds for classes beyond that.

Students will now be required to earn a scaled score of 486 on the English and math exams (or 470 with the completion of an educational proficiency plan) and meet a threshold set at 470 for science and technology/engineering tests. The score thresholds are currently 472 for English, or 455 with an educational proficiency plan, 486 for math, or 469 with an educational proficiency plan, and 220 for science/technology for students who took a test by February 2020.

Riley previously told the board that research shows "MCAS scores predict later outcomes in education and earnings" and that "only 11% [of] students in the class of 2011 who scored at the current passing standard in mathematics went on to enroll in a four-year college in Massachusetts, and only 5% graduated from a four-year college within seven years."

"This evidence underscores the importance of raising the [competency determination] standard and also highlights the need to articulate clearly to students, parents, educators, and other stakeholders how the different levels of achievement on the MCAS tests -- and in particular the CD level -- signal whether a student is on track for success beyond high school, whether in postsecondary education, the military, the workplace, or independent and productive community life," Riley wrote in a memo to the board. "Raising the CD standard is critical, as is the message that we believe students are capable of meeting the higher standard and the Commonwealth and its educators will support them to do that."

Lawmakers created the MCAS system in a 1993 education reform law aimed at improving accountability and school performance. The first tests were administered in 1998, and students have been required to achieve sufficient scores to graduate since the class of 2003.

Most students take the tests linked to graduation in 10th grade, though they can retake exams up to four more times if they do not score high enough. MCAS has long been a controversial test and measurement of student achievement, with opponents arguing that setting the exams as a bar all students must clear forces teachers to narrow their focus on test preparation and creates unnecessary stress in the classroom.

The majority of public comments the board heard Monday were from people opposed to raising the thresholds that determine whether a high school student scored well enough on the MCAS standardized test to pass. Among those to testify against Riley's recommendation Monday were Rep. Jim Hawkins and Sens. Patricia Jehlen and Jo Comerford.

Hawkins, who taught math at Attleboro High School for 12 years, said he's afraid that higher MCAS passing standards will mean that more students will have to take remedial courses instead of being able to pursue something that truly interests them.

"You go through school, first few grades are all the same, the same, the same. And when you get to be a junior, senior in high school, you get to take the courses that really energize you, whether it be music, arts, vocational trades, whatever it is. If these students don't pass the MCAS in 10th grade and then have to take remedial courses instead of the courses that motivate them -- especially in low-income communities, children who are struggling to get by -- these are the courses that motivate them and we're taking them away from them if they haven't passed the MCAS," he said.

Hawkins and Comerford this session filed a bill (S 293 / H 612) that would have decoupled MCAS from graduation and instead offered other pathways for students to prove they meet the benchmarks to complete high school, some of which would not have required a standardized test. That bill was sent to a dead-end study by the Education Committee, but Hawkins told the Sun Chronicle in June that he plans to refile the legislation next session.

Jehlen, of Somerville, urged the board not to accept Riley's recommendation and said that "raising the passing score for English MCAS will harm children who are English learners," a cohort that she said is the fastest-growing group of students in Massachusetts schools at more than 100,000 students or 11 percent of statewide enrollment.

"These children will be the ones most affected by raising the English passing scores because, by definition, they don't yet read and write English fluently. They can have bright futures as important members of our community and contributors to our economy if they can get a high school diploma," she said.

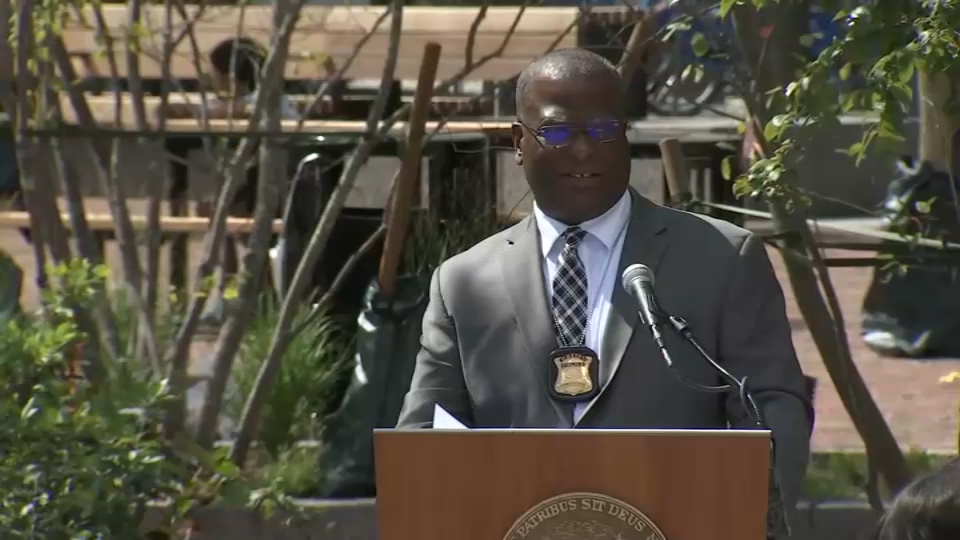

Monday's vote was also bashed by Max Page, president of the 115,000-member Massachusetts Teachers Association, who said he was not there to plead for members to reject the recommendation since "you've already made pretty clear in public and no doubt in private meetings that you intend to" adopt it.

"You've fetishized an approach to education that is, at the very least, outdated and, at the most, destructive of our schools and communities. You know, somewhere a little before the ed reform bill in 1983, I had a shiny object I too thought was magical. It was called a mood ring and I thought it was capturing my every change of emotion. I also thought that REO Speedwagon's first album was really the height of pop music. Then I grew older and I grew up," Page said. "The board is still fidgeting with your mood rings and spinning their REO Speedwagon albums, obsessed with a test invented some 20 years ago and repeatedly shown to do little more than prove the wealth of the student and the community where it is taken."

He said he was "actually looking beyond this meeting today" and wanted board members to know that the MTA, its supporters and other activists "will stay committed until each of you who continue to reinforce this high-stakes testing regime have moved on to other places, and we replaced you with people who will reverse this two decades-long travesty."