Brian Walshe due in court today for hearing

Brian Walshe, the Cohasset, Massachusetts, man accused in the alleged murder of his wife, Ana Walshe, is scheduled to be in court today.

Brian Walshe, the Cohasset, Massachusetts, man accused in the alleged murder of his wife, Ana Walshe, is scheduled to be in court today.

The Red Sox promoted D’Angelo Ortiz, the son of Hall of Famer David Ortiz, to Low-A Salem on Wednesday.

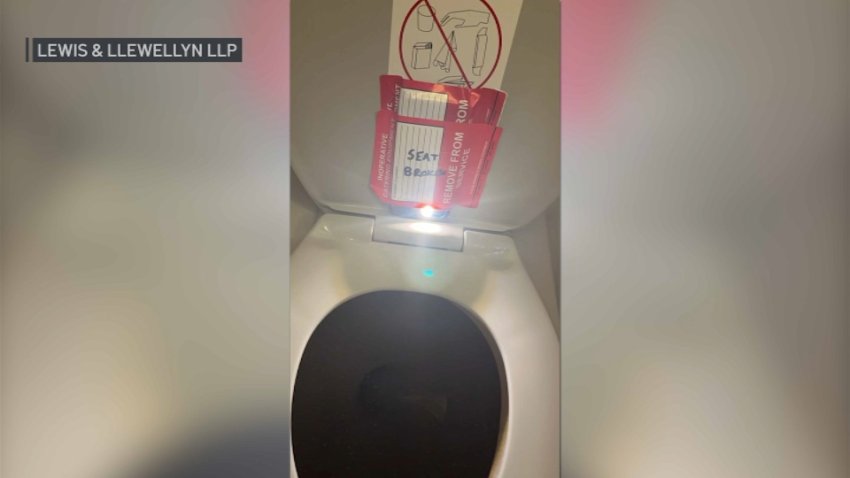

A flight attendant accused of taping his cellphone to the lid of an airplane toilet to secretly film young girls was sentenced to just under 20 years in prison Wednesday.

Tom E. Curran and Phil Perry discuss what they saw from Patriots rookie wide receiver Kyle Williams on Day 1 of training camp.

A child was rushed to a hospital after being reported not breathing in Roxbury Wednesday morning, Boston police said.

A driver has been charged a year after he hit and killed a woman walking her bicycle near a Bedford, Massachusetts, bike path, officials said Wednesday.

Police say they’ve caught a person connected to the theft of over $100,000 in rare Pokémon cards from a Massachusetts collectibles store.

The City of Boston will start issuing code enforcement fines directly to Republic Services for garbage left uncollected amid the ongoing trash collection worker strike, Mayor Michelle Wu said in a letter on Wednesday.

Hundreds of attorneys stopped taking new court-appointed cases in May to protest their pay rates, which they say are far lower than neighboring states

Phil Perry spotlights the Patriots players who shined and those who struggled Wednesday on Day 1 of training camp.

Drake Maye set the tone both on the field and at the podium during Day 1 of Patriots training camp, writes Phil Perry.

A Natick man says Iberia Airlines downgraded his seats, then denied the claim for the $700 difference multiple times.

The workers, represented by UNITE HERE Local 26, said that they are paid less at Fenway than at other locations serviced by Aramark, including Boston University and other stadiums across the country.

Police shut down a street in Worcester, Massachusetts, Wednesday to investigate a potential threat involving weapons posted on social media, officials said.