U.S. health and agriculture officials are ramping up testing and tracking of bird flu in dairy cows in an urgent effort to understand — and stop — the growing outbreak.

So far, the risk to humans remains low, officials said, but scientists are wary that the virus could change to spread more easily among people.

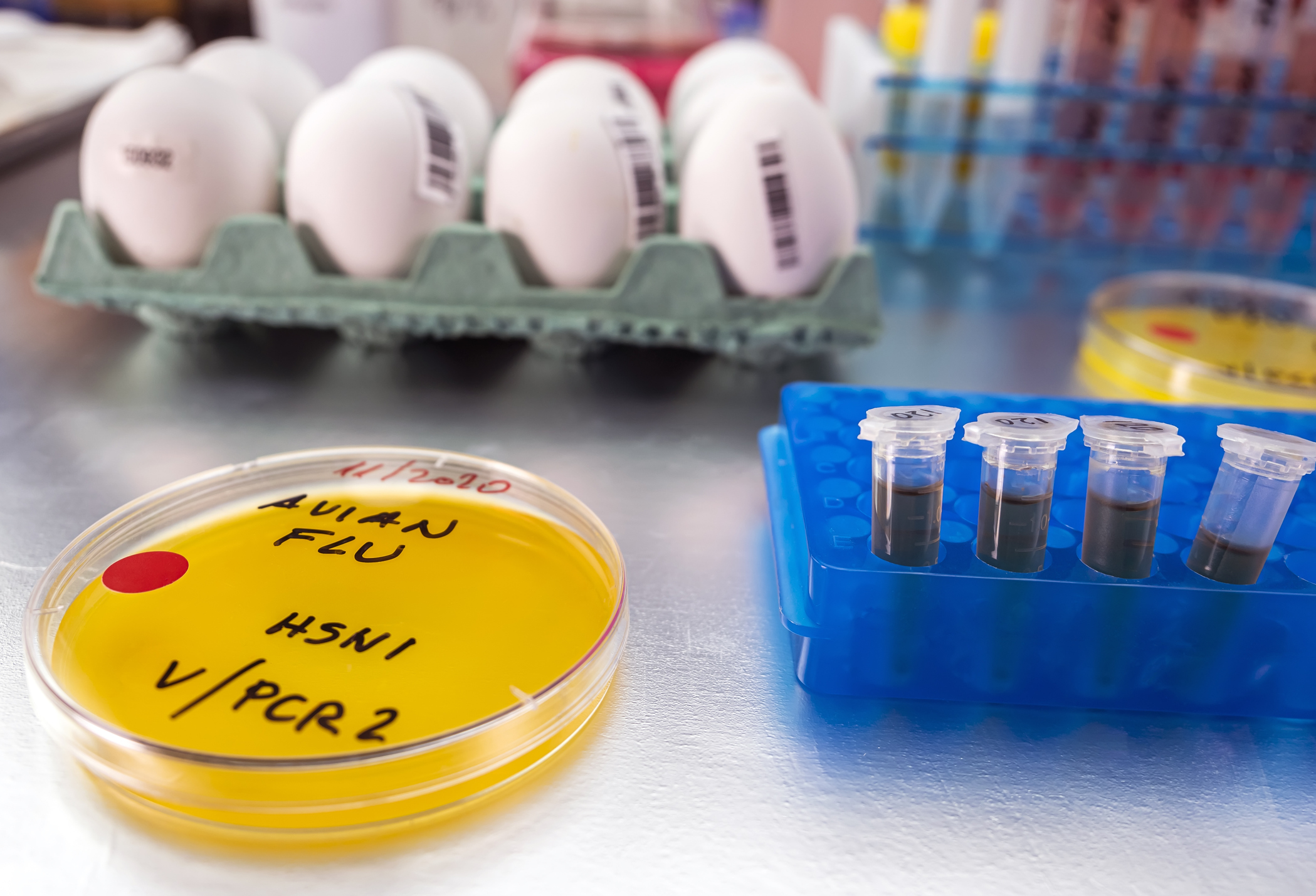

The virus, known as Type A H5N1, has been detected in nearly three dozen dairy herds in eight states. Inactive viral remnants have been found in grocery store milk. Tests also show the virus is spreading between cows, including those that don't show symptoms, and between cows and birds, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Starting Monday, hundreds of thousands of lactating dairy cows in the U.S. will have to be tested — with negative results — before they can be moved between states, under terms of a new federal order.

Here's what you need to know about the ongoing bird flu investigation:

Why is this outbreak so unusual?

This strain of what's known as highly pathogenic avian influenza has been circulating in wild birds for decades. In recent years, it has been detected in scores of mammals around the world. Most have been wild animals, such as foxes and bears, that ate sick or dying birds. But it's also appeared in farmed minks. It's shown up in aquatic mammals, such as harbor seals and porpoises, too. The virus was even found in a polar bear in northern Alaska.

The virus was discovered in ruminants — goats and then dairy cows — in the U.S. this spring, surprising many scientists who have studied it for years.

“When we think of influenza A, cows are not typically in that conversation,” said Richard Webby, an influenza expert at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

How long has bird flu been spreading in cows?

Flu viruses are notorious for adapting to spread among new species, so detection in dairy cows raises concerns it could spread to people, Webby said.

Scientists confirmed the virus in cows in March after weeks of reports from dairy farms that the animals were falling ill. Symptoms included lethargy, sharply reduced milk supply and changes to the milk, which became thick and yellow.

Finding remnants of the virus in milk on the market “suggests that this has been going on longer, and is more widespread, than we have previously recognized,” said Matthew Aliota, a veterinary medicine researcher at the University of Minnesota.

Under pressure from scientists, USDA officials released new genetic data about the outbreak this week.

The data omitted some information about when and where samples were collected, but showed that the virus likely was spread by birds to cattle late last year, said Michael Worobey, an evolutionary biologist with the University of Arizona.

Since then, it has spread among cattle and among farms, likely through contact with physical objects such as workers' shoes, trucks or milking machines, Worobey said.

And then the cows spread the virus back to birds, he said.

“The genetic evidence is as clear as could be,” Worobey said. "Birds that are sampled on these farms have viruses with clear mammalian adaptations."

What do scientists say about efforts to track the outbreak?

Several experts said the USDA's plans to require testing in cows are a good start.

“We need to be able to do greater surveillance so that we know what's going on,” said Thomas Friedrich, a virology professor at the University of Wisconsin's veterinary school.

Worobey said the ideal would be to screen every herd. Besides looking for active infections, agriculture officials also should be looking at whether cows have antibodies to the virus, indicating past infections, he said.

"That is a really accessible and quick way to find out how widespread this is,” he said.

More testing of workers exposed to infected animals is also crucial, experts said. Some farm owners and some individual workers have been reluctant to work with public health officials during the outbreak, experts have said.

“Increased surveillance is essentially an early warning system,” Aliota said. “It helps to characterize the scope of the problem, but also to head off potentially adverse consequences."

How big a risk does bird flu pose for people?

Scientists are working to analyze more samples of retail milk to confirm that pasteurization, or heat-treating, kills the H5N1 virus, said Dr. Don Prater, acting director of the FDA's food safety center. Those results are expected soon.

While the general public doesn't need to worry about drinking pasteurized milk, experts said they should avoid raw or unpasteurized milk.

Also, dairy farm workers should consider extra precautions, such as masking, hand washing and changing work clothes, Aliota said.

So far, 23 people have been tested for the virus during the outbreak in dairy cows, with one person testing positive for a mild eye infection, CDC officials said. At least 44 people who were exposed to infected animals in the current outbreak are being monitored for symptoms.

What are scientists' concerns for the future?

David O’Connor, a virology expert at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, likened recent bird flu developments to a tornado watch versus a warning.

“There are some of the ingredients that would be necessary for there to be a threat, but we’re not there,” he said. As with a tornado watch, "you wouldn’t change anything about how you live your daily life, but you would maybe just have a bit of increased awareness that something is happening.”

Worobey said this is the kind of outbreak “that we were hoping, after COVID, would not go unnoticed. But it has."

He said ambitious screening is needed "to detect things like this very quickly, and potentially nip them in the bud.”

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.