The Washington chattering class, often unsure what to make of outsiders, dubbed Rosalynn Carter the “Steel Magnolia” when she arrived as first lady.

A devout Baptist and mother of four, she was diminutive and outwardly shy, with a soft smile and softer Southern accent. That was the “magnolia.” She also was a force behind Jimmy Carter’s rise from peanut farmer to winner of the 1976 presidential election. That was the “steel.”

Yet that obvious, even trite moniker almost certainly undersold her role and impact across the Carters’ early life, their one White House term and their four decades afterward as global humanitarians advocating peace, democracy and the eradication of disease.

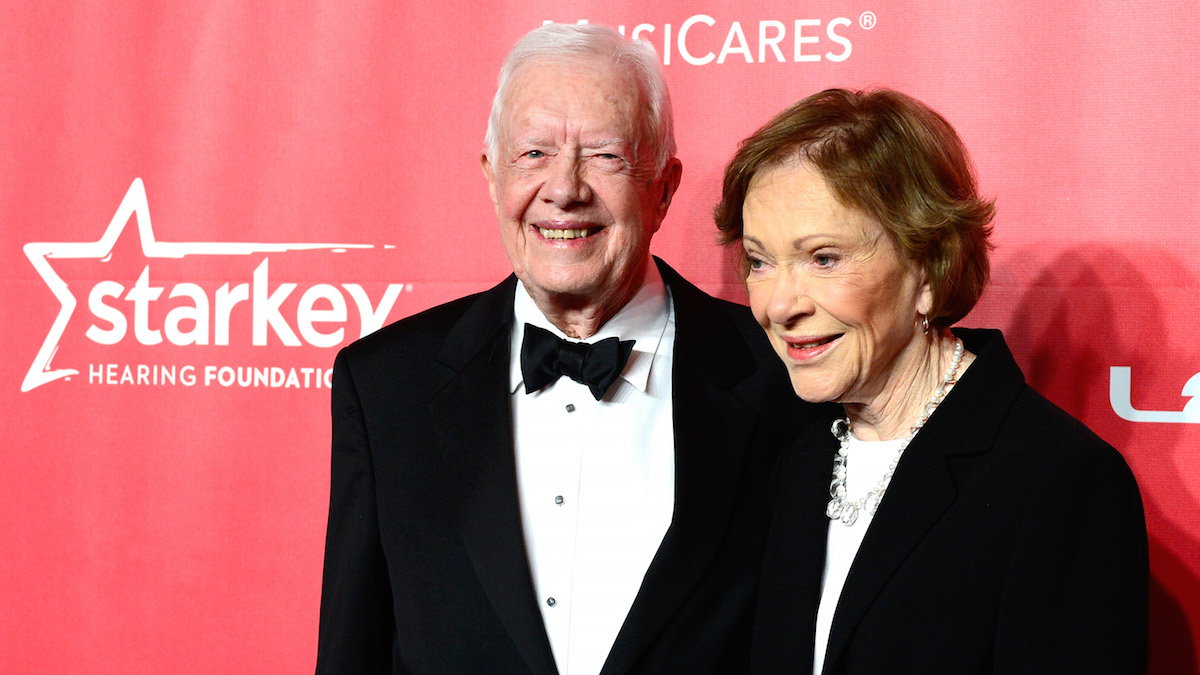

Through more than 77 years of marriage, until her death Sunday at the age of 96, Rosalynn Carter was business and political partner, best friend and closest confidant to the 39th president. A Georgia Democrat like her husband, she became in her own right a leading advocate for people with mental health conditions and family caregivers in American life, and she joined the former president as co-founder of The Carter Center, where they set a new standard for what first couples can accomplish after yielding power.

“She was always eager to help his agenda, but she knew what she wanted to accomplish,” said Kathy Cade, a White House adviser to the first lady and later a Carter Center board member.

Rosalynn Carter talked often of her passion for politics. “I love campaigning,” she told The Associated Press in 2021. She acknowledged how devastated she was when voters delivered a landslide rebuke in 1980.

Cade said a larger purpose, though, undergirded the thrills and disappointments: “She really wanted to use the influence she had to help people.”

Jimmy Carter biographer Jonathan Alter argues that only Eleanor Roosevelt and Hillary Clinton rival Rosalynn Carter's influence as first lady. The Carters’ work beyond the White House, he says, sets her apart as having achieved “one of the great political partnerships in American history.”

Cade recalled her old boss as “pragmatic” and “astute,” knowing when to lobby congressional brokers without her husband’s prompting and when to hit the campaign trail alone. She did that for long stretches in 1980 when the president remained at the White House trying to free American hostages in Iran, something he managed only after losing to Ronald Reagan.

“I was in all the states,” Rosalynn Carter told the AP. “I campaigned solid every day the last time we ran.”

She flouted stereotypes of first ladies as hostesses and fashion mavens: She bought dresses off the rack and established an East Wing office with her own staff and initiatives — a push that culminated in the Mental Health Systems Act of 1980 to steer more federal money to treating mental health, though Reagan reversed course. At The Carter Center, she launched a fellowship for journalists to pursue better coverage of mental health issues.

She attended Cabinet meetings and testified before Congress. Even when fulfilling traditional responsibilities, she expanded the first lady's role, helping to establish the regular music productions still broadcast as public television’s “In Performance at the White House.” She presided over the inaugural Kennedy Center Honors, prestigious annual awards that still recognize seminal contributions to American culture. She hosted White House dinners but danced only with her husband.

Her approach befuddled some Washington observers.

“There was still a women’s page in the newspaper,” Cade recalled. “The reporters who were on the national scene didn’t think it was their job to cover what she was doing. She belonged on the women’s page. And the women’s page folks had difficulty understanding what she was doing, because she wasn’t doing the more traditional first lady things.”

Grandson Jason Carter, now Carter Center board chairman, described her “determination that never stopped.” She was “physically small” but “the strongest, most remarkably tough woman that you would ever hope to see.”

Including as Jimmy Carter’s political enforcer.

She “defended my grandfather in a lot of contexts, including against Democrats and others,” confronting, in person or via telephone, people she thought had damaged his cause, Jason Carter said.

“There are certainly stories out there of her — despite her reputation as quiet-spoken — cursing a blue streak at folks who said bad things about my grandfather,” he added, laughing as he imagined his grandmother threatening befuddled power players with “a string of F-bombs.”

The younger Carter, himself a one-time Georgia state senator and unsuccessful candidate for governor, called her “the best politician in the family.”

Yet she nearly always connected politics to policy and those policy outcomes to people’s lives — connections forged from her earliest years in the Depression-era Deep South.

Eleanor Rosalynn Smith was born Aug. 18, 1927, in Plains, delivered by nurse Lillian Carter, a neighbor. “Miss Lillian” brought her son, Jimmy, then almost 3, back to the Smith home a few days later to meet the baby.

Not long after, James Earl Carter Sr. moved his family to a farm outside Plains. But the Carter and Smith children attended the same all-white schools in town. Years later, Rosalynn and Jimmy would quietly support integration — and call for it more vocally at Plains Baptist Church. But growing up, they accepted Jim Crow segregation as the order of the day, she wrote in a memoir.

Rosalynn and Jimmy each endured challenges of rural Depression life. But while the Carters were considerable landholders, the Smiths were poor, and Rosalynn’s father died in 1940, leaving her to help raise her siblings. She recalled this period as inspiration for her emphasis on caregivers, a way of classifying people that Alter, the biographer, said was not used widely in discussions of American society and the economy until Rosalynn Carter used her platform.

“There are only four kinds of people in this world,” she said. “Those who have been caregivers; those who are currently caregivers; those who will be caregivers, and those who will need caregivers.”

As she grew up, Rosalynn became close to one of Jimmy’s sisters. Ruth Carter later engineered a date between her brother and Rosalynn during one of his trips home from the U.S. Naval Academy during World War II. Jimmy, newly commissioned as a Navy lieutenant, and Rosalynn were married July 7, 1946, at Plains Methodist Church, her home church before she joined his Baptist faith.

Rosalynn had been a bright student in high school and at nearby Georgia Southwestern College. She contemplated becoming an architect but explained later that, beyond simply falling in love with Jimmy, marrying a Naval officer was the best path for what she wanted most: to leave her hometown of about 600 people.

As Jimmy's career advanced, Rosalynn took care of their growing family. When Earl Carter, by then a state lawmaker, died in 1953, Jimmy decided to leave the Navy and move the family home to Plains. He did not consult Rosalynn. On their long car ride back from Washington, she gave him the silent treatment, talking to him only through their eldest son.

What they would later call a “full partnership” did not sprout until a few years later, when a desperate Jimmy asked Rosalynn to answer phones at the peanut farm's warehouse. She was soon managing the books and dealing with customers.

“I knew more on paper about the business than he did, and he would take my advice about things,” she recalled to the AP.

The lesson did not immediately carry over to Jimmy's political ambitions.

Already an appointed school board member, he decided to run for state Senate in 1962, again without consulting Rosalynn. This time, she embraced the decision because she shared his goals.

Four years later, Jimmy ran for governor, giving Rosalynn the first chance to campaign by herself. He lost. But they spent the ensuing four years preparing for another bid, traveling the state together and separately, with a network of friends and supporters. It would become the model for the “Peanut Brigade” they used to blanket Iowa and other key states in the 1976 Democratic primary season.

Those campaigns for governor solidified mental health as Rosalynn's signature issue.

Voters “would stand patiently” waiting to tell of their family struggles, she once wrote. After hearing one overnight mill worker’s story of caring for her afflicted child, Rosalynn decided to take the issue to the candidate. She showed up at her husband’s rally that day, unannounced, and stood in line to shake his hand like everyone else.

“I want to know what you are going to do about mental health when you are governor,” she asked him. His reply: “We’re going to have the best mental health system in the country, and I’m going to put you in charge of it.”

By the time they got to the White House, Rosalynn had distinguished herself as the center of Carter’s inner circle, even if those beyond the West Wing did not appreciate her role.

“Unlike many first ladies, she didn’t quarrel with the White House staff, because they thought she was fantastic,” Alter said, calling her relationship with staff smoother than the president’s.

Carter sent her on diplomatic missions. She took Spanish lessons to aid her Latin America voyages. She decided herself to travel in 1979 to Cambodian refugee camps. Spurred by a Friday briefing, she was on a plane the next week, having put together an international delegation to address the crisis.

“She wasn’t just going to have pictures made ... she watched people die,” Cade said.

The first lady worked closely with policy chief Stu Eizenstat on mental health legislation but did not confine herself to her own priorities.

“She did a lot of very quiet and behind-the-scenes lobbying” of congressional figures concerning the administration agenda, Cade recalled, but she “was very firm about the fact that we never talked about who she was calling” so that she would never upstage the president.

She traveled to U.S. state capitals and urged lawmakers to adopt vaccine requirements for schoolchildren, winning over converts to policies that largely remain intact today, recent fights over COVID-19 vaccine mandates notwithstanding.

She was involved throughout intense negotiations at Camp David with Egyptian leader Anwar Sadat and Israel’s Menachem Begin, both of whom warmed to the first lady.

Jimmy’s mother, who lived at the White House, sometimes rankled her daughter-in-law by seeming to posture as the home’s lead hostess. But Lillian Carter plainly acknowledged the pecking order. The president “listens to her,” Miss Lillian told reporters.

Not always, of course.

Rosalynn wanted her husband to delay the treaty ceding control of the Panama Canal, pushing it to a second term. She met regularly, without the president, with pollster Pat Caddell. They discussed a reelection path she knew was perilous on the heels of inflation, rising interest rates, oil shortages and the Iran hostage situation.

Distraught upon their return to Plains in 1981, she dived back into the farming business. But the void would not begin to close until the former president conceived The Carter Center. In their Atlanta outpost, she found an enduring platform from which to travel the world, pushing to eradicate Guinea worm disease and other maladies in developing countries, monitoring elections, elevating discussion of women’s and girls’ rights and continuing her mental health advocacy. All while living in the same Georgia village she once wanted to leave forever.

“My grandparents, you know, have a microwave from 1982. ... They’ve got a rack next to their sink where they dry Ziploc bags, reuse them,” Jason Carter said recently, explaining their “simple” and “frugal” style in the same home where the Carters lived when Jimmy was first elected as a state senator.

There, the former first lady welcomed foreign dignitaries, President Joe Biden and first lady Jill Biden, aspiring politicians seeking advice and, as her health declined, a new generation of Carter Center leadership. She liked to serve pimento cheese sandwiches, fruit and, depending on the guest list, a few glasses of wine. And she came with an agenda.

“Mrs. Carter would always be the first one at the door, and she would insist on walking me to the door at the end,” Carter Center CEO Paige Alexander said of her sessions in Plains. “That final walk ... so she could get her last points in was, I think, quite indicative of the relationship that they had and how she managed it from the Governor’s Mansion all the way through.”